Kirsha was interviewed by Elizabeth Pearce, Mona Research Curator and Senior Writer, in July 2016.

EP: Why are you opening a hacking school?

KK: It seemed like a good evolution of my CA$H 4 GUN$ project. At first I thought it would be fun to do as a conceptual artwork, but I wasn’t serious—it seemed a bit too Black Panthers. Although, now that I say that, I realise that Robert Trivers, the evolutionary biologist who is one of our hacking school’s spiritual guides, actually was a Black Panther. He got excommunicated ‘for his own good’. Anyway, a hacking school sounds dangerous and exciting, and is therefore attractive to at-risk youth. I mean, these guys are literally killing each other and selling crack, so it’s not like they are going to sign up for your feel good, let’s-all-love-one-another self-improvement program. Basically I want to overthrow traditional ideas of what social work looks like—ugly. And what social programs feel like—dorky and boring. It’s tech education disguised as a hacking program—housed in a secret, Dr-Strangelove-meets-James-Bond villain lair.

EP: I am always trying to work out where the line is in your projects between art and social justice.

KK: I can't do it if it's ugly. I'm completely uninterested in social work that is not simultaneously aesthetic, and simultaneously an interesting conceptual artwork. This is important because it impacts what I am able to give… I mean, it’s not really my giving, it’s David’s giving. But the level to which I am prepared to manipulate him into doing what I want is directly tied to how aesthetically rewarding the project is. So if we're going to have a garden program—yeah, okay, I'll get behind a garden program. But I probably won't really start to drive it and expand it to new communities and put all that effort in unless I feel like it's an inspiring, radical reinvention of what a garden program looks like. The basest part of me wants to be at a five-star hotel lapping up luxury treatments at the spa. I can redirect that drive to social work if it becomes art, and if it becomes an engine for societal reinvention.

EP: I find this aspect of your work unique. The art component is basically the carrot to the social work stick. I tried to write something about it, and I found I didn’t understand enough about it, which is why I’m doing this interview.

KK: I do find it a bit offensive that these social projects are so ugly. Why is that fair? I'm not going to go and help this disadvantaged community by putting in some really depressing venetian blinds, and fluorescent light that makes you want to kill yourself. I understand that I'm a very aesthetics-driven person. So I'm projecting my own feelings about spaces I want to be in, or programs I want to be a part of, onto the community that I'm assisting.

EP: Isn’t that what art is? Projecting your own ideas about the world? The difference here is that the art is tweaked to have more tangible benefits. It’s funny, because if you were doing something that was pure art, and not intended to help anyone, you’d never be criticised.

KK: Yes, that's true. At least my art has some social benefit. Look at Rouge Battery (2014). There's $1 million just sitting there in the gallery, doing nothing.*

Granted, art like this can expand the minds of the people who see it. But they have to get to the gallery first, and many disadvantaged people won't be able to do that. If you can justify Rouge Battery, then you could certainly justify a dream of creating shared, beautiful experiences with parts of the community that have been denied access to those things.

EP: People have an instinctive, but perhaps unjustified, hierarchy of what's valuable and truthful. Things that are beautiful are ‘only’ beautiful—they are shallow, deceitful somehow. They say, ‘She only got the job because she is good looking,’ but they never say ‘She only got the job because she’s intelligent.’ In fact, both qualities can be equally in-born or developed over the life span. Both are valid parts of who a person is.

KK: Or, ‘She’s only married to David Walsh because she’s hot.’

EP: Exactly.

KK: Except that I'm kind of normal looking.

EP: Probably towards the hot end of the scale.

KK: The hot end of normal.

EP: I love it when you laugh at your own jokes. Did you get that from Amélie? [a mutual friend]

KK: Amélie was supposed to work out with me today but she couldn’t because she was on acid. We had a gym date and she sent a text: ‘Sorry, can't run. On acid.’

EP: In the middle of the day?

KK: At nine in the morning.

EP: That makes it better.

KK: Well, it's closer to the night.

EP: Do you find that you often have to justify your art-as-social-work to critics?

KK: Not that many people notice that it’s problematic. People in New Orleans noticed. They didn't like the class mash-up. But that was part of what I was trying to achieve. When I first moved [to the St Roch neighbourhood of New Orleans’ 8th Ward] and started growing vegetables with the kids, my foundation, Life is Art, was very small. I didn't have a bus or a driver. I'm illegally packing the kids into my car, and driving them to restaurants to sell their produce. If I'm going to spend my time doing that, I'm sorry, but I don't want to go to a crummy restaurant. I figured it would be a lot nicer to go to the best restaurants in New Orleans. At the same time, it was really important to me that the kids in my neighbourhood would feel confident waltzing into these chandelier-laden places, befriending the chefs, feeling confident with the wait staff, and being able to say, ‘I've got a product that's better than your normal restaurant supplier. It's organic. It was picked twenty minutes ago.’ So while I'm enjoying a nice atmosphere with chefs I relate to, in a stratum of society that I enjoy, the kids are also breaking down their fear and the sense that they've been disowned by that tier of society. They walk in and become the boss. If we were going to low-end neighbourhood joints I don't feel it would have been as successful at dissolving the social divide.

EP: It would also be less honest, because when people ‘do good’ they fool themselves into thinking it’s purely selfless. But you and I know that altruism and selfishness are actually mutually constitutive. People’s motivations are complex.

KK: Footnote: See On the Origin of Art.

EP: Exactly. You just did a verbal footnote, by the way. That's good. But what I mean is that we know human emotion is structured to get a particular outcome that benefits the self, no matter how altruistic the means to that end.

KK: Well, we don't necessarily know that… At the same time that I'm a science-based rationalist, I am a bit of a new-age spiritualist hippie. There is this idea of the bodhisattva, which is that when you attain enlightenment you don't need to deal with the physical dimension anymore. You're over it. Once you've reached that level, you come back in physical form—which sucks, but you do it because you want to help humanity. You want to bring them with you, help enlighten them, so that they, too, can transcend this plane. I do believe in this ideal self in a freely giving, pure-hearted state—the potential me. But at the same time I am here in the world and my time is limited. I certainly would like to spend my time trying to bring opportunity, richness of experience, and justice to underprivileged communities, but I still want to drive a Tesla. I don’t really struggle with this, but I think David does. He's got real guilt about his wealth. I don't mind my personal privilege—I see it as a wonderful opportunity for helping restructure society.

EP: I want to go back a bit now. How is it that you came to grow up in Guam?

KK: My dad left his job [as an engineer with the RAND Corporation] in part because of his psychedelic exploration with LSD. That opened him up to alternative interests, the main one being rolfing, which sounds like barfing. My mother was a painter and a nurse practitioner who harboured tropical fantasies—our whole house was decked out in rattan and palm prints. She knew a woman from Guam, so they decided to go for six months, just for fun. My dad died there, and my mother still lives there. I was five when we moved, and they enrolled me in kindergarten. I had to sing the Guam anthem in Chamorro every morning. The first words I picked out were ‘pee potty’, which was really ‘Abiba i’—as in, ‘Abiba i isla sen paarat’. It means ‘Exalt our isle forever more’.

EP: Did you have a sense of being an expat?

KK: I noticed I was different once I got to school, when being white became more of an issue. I was very much a minority and teased constantly—‘white-hair girl’, ‘howlie’, ‘honkie bitch’. I used to tape my eyes to make them more slanted and push my nose down, wishing it were flatter. When I got older I couldn’t get a boyfriend until I found a Mexican military guy. That was excruciating because everyone in Guam hates the military, including me, but he was the only brown guy who would date me. I wouldn’t dream of touching a white guy. They were total outcasts. I didn’t think I’d ever have a white boyfriend. At the same time the brown guys didn't like me because I was white. So it was a bit of a problem, until I found my Mexican.

When your dad died—I read this on Wikipedia—you travelled to fifty countries in a seven-year period?

KK: Yeah.

EP: What were you looking for?

KK: Enlightenment.

EP: What did you think that might look like?

KK: It came in all kinds of packages. I believed that if you surrender fully to the moment, with an open heart, life will unfold. For instance, I was in a health food store in Maui and made eye contact with this woman across the other side of the room. When you're a new ager, and you see a fellow spiritualist, you recognise each other—you just know. We met in the middle of the store and hugged, and she invited me to her commune. They were sannyasins, devotees of [the Indian mystic] Rajneesh—you know, that guy who had the ninety-nine Rolls Royces. Sannyasins are really fun—they know how to live. I considered joining their cult but I watched this video of Rajneesh, and he was like, ‘Life is so beautiful...sh’. He would put this ‘sh’ sound at the end of every sentence. I thought, this guy’s on downers! He’s on pills. I couldn’t get into him. He made a great tape, though, called ‘the fuck tape’, that I liked a lot. And I do still use his outfits for inspiration in my projects today.

EP: What else did you try?

KK: All kinds of things. I was very interested in shamanism, so I took ayahuasca in Santa Cruz and then went down to the Amazon.

EP: That's a hallucinogen?

KK: It's a really hard-core hallucinogen, made from a vine and a leaf. Shamanism takes different forms, and I explored other forms that are not drug dependent, but this particular form relied on a drug experience—‘medicine’ as we would say. You enter this experience—it can last eight hours—and all preconceptions of reality are broken down. Interesting things happen. For instance, I was able to heal my relationship with my mother for a number of years.

EP: How?

KK: I understood that she was a part of me and that we were one, and that she was playing a particular role for me. The main realisation [with that drug] is that there is no ‘other’. All the spiritual practices talk about that, but you really experience it on ayahuasca. The one-ness of the universe, the ‘is’-ness, means that we are always playing roles for each other to help each other learn, and to experience ourselves. The realisation was that my mother was so generous for enacting this very difficult role for me—I had immense gratitude towards her. It only lasted a couple of years, but that’s a pretty good return on an eight-hour trip.

EP: You obviously turned away from shamanism?

KK: I got kicked out. On my fifth ayahuasca experience I was sitting in the jungle on the dirt floor of this hut with the shaman, who had just complimented me on my ability to go with the experience—because there was a French guy there too, who was flipping out, screaming his head off. The shamans were shoving lemons in his mouth to try to bring him back to reality—the shock of the acid.

EP: That's awesome.

KK: I was feeling like such a good shaman student by comparison. I was being eaten by alligators—the visions are really extreme. You have to die every time, in one way or another. So I'm being consumed by alligators, eaten by earthworms and beetles—it's all happening and I'm cool with it, cool with death. Then all of a sudden—boom. It just stopped. I'm stone cold sober, except for this one vision—which is me on a plane, and this very firm message: ‘You need to go back to the West.’ And so commenced the most difficult phase of my life in terms of, I suppose, being human. That was my existential crisis. I felt like I'd been ousted from my mission.

EP: You hadn't found what you were looking for?

KK: No, I hadn't. I felt like a failure for being stuck in this dimension, and still having a self. I couldn’t handle society. So then art, in the form of little creative projects, was what got me through. In the creative process I would dissolve into the work, but there was a beginning and an end. That helped me be in the world.

EP: Can I have an example?

KK: Early on it would be something as simple as… there's a party. Let's do a performance with costumes—white feathers or fluoro spandex or hula hoops or something. So that meant searching in op shops with my friends and doing some sewing, and then choreographing a routine. Doing all this meant I was in the world. It helped me feel happy and alive and like I could reach that state of self-dissolution, while also being a member of society. My friend Mat Vis and I formed a group called ART (About Realizing Truth), so the existential struggle itself became art.

EP: You have this group of friends now—you kind of all understand each other, you have this sort of synthesis.

KK: Yep, they’re all acid heads. It’s an irreverence for reality.**

EP: Where did your funding come from?

KK: Well, I had an inheritance, but mostly you could get by with hardly any money. A lot of my artist friends in New Orleans were strippers and some turned that into performance art. I tried—I sewed a costume and everything, silver lame—but on my first night I just couldn’t do it. That was disappointing because I felt like you haven’t lived until you’ve been a stripper. In Maui, though, it was more that there was money somewhere in the background. Some of the people in the scene were heirs. They would support their poor friends and we would all share each other’s income. That's my model for philanthropy. The people who have the means, their lives are boring if they just sit on their estates. They need these beautiful people to come to their land and grow gorgeous food and do art projects and sell magical fairy dresses and blow glass and do whatever they do, massage or healing or shamanic work. So their life is enhanced by the presence of that community and the community then doesn't have to worry about money.

EP: That explains a lot actually because I've often wondered… There’s this whole group of you, and its not like any of you are actually selling art.

KK: No. Occasionally there'll be a transaction. I sold my car once, but then I never cashed the cheque. Going into a bank is such an aesthetically void experience. So I can't participate.

EP: ‘I am so aesthetically voided by this experience. Can someone please serve me right now so I can get out of here?’

KK: Yeah. I've had sugar daddies on both sides of my life, but there was definitely an in-between time when I was poor.

EP: On the one hand there's this image of you as this fashionable, privileged woman living and working in the heart of one the most underprivileged neighbourhoods in New Orleans. But also as an artist, you’re very post-object. The idea of making an object as art, and selling it…

KK: Totally repulsive. Only if it were a joke, or a performance.

EP: Why did you feel compelled to establish the Life is Art foundation?

KK: It sort of established itself. We were just playing around, and it got popular. I loved throwing parties, and lots of people came. A few patrons offered to sponsor projects—some of them needed a non-profit. I started to get more structured, and I tried to attract more patrons.

EP: Why did you choose New Orleans as the home of Life is Art?

KK: I didn't. I had planned to go to Cuba to join a raft of refugees, to document the experience. I was on my way to do that and I stopped in New Orleans. I think a tarot reader in New York City told me to go south, go to where the palm trees were. I had just come back from Lebanon…

EP: What were you doing in Lebanon?

KK: It's a whole can of worms but basically I was living with a Hezbollah family and writing a book. But anyway, I ended up in New Orleans, intending to stop there briefly. I landed in the middle of Mardi Gras. There were no hotels or hostels, nowhere to stay. A taxi driver knew of some kind of motorcycle hangout and they had a room at this really grungy place. I still think of their ‘86 list’—a poster of all the people banned from their establishment. You really had to be someone to get banned from that place. It was an incredible work of accidental art. Anyway, I'm watching Mardi Gras unfold—which is outrageous. I meet these crazy artists, people from the 9th Ward Marching Band, which I later joined, and Quintron and Miss Pussycat. They invite me to this party at a guy named MC Trachiotomy’s house, which was also a secret bar called The Pearl. (I later became a back-up dancer for him, and for Quintron and Miss Pussycat as well.) It was so weird. It had no floor. So you'd walk into this 1800s mansion and then suddenly you have to step down to the dirt level. I was so out of my depth and so uncool, because I was unsocialised.

EP: You were the uncool white girl again?

KK: I was a seriously uncool white girl. Guys sitting on the corner would say something and I would say, ‘What?’ and they'd be like, ‘Girl, you gotta learn to talk black.’ So I decided to rent a place for at a few days and that turned into weeks, and I was like, ‘I've been wandering for years. This is the first place where I feel like I have got to stick around and learn, to get my head around what's going on.’

EP: So why did you choose that particular site in the St Roch neighbourhood for your foundation? It was a series of run-down buildings, right?

KK: I'd been told not to ride my bike in that area. So of course after a while I decided I just had to ride my bike there.

EP: Because it was too dangerous?

KK: Yeah, but keep in mind I've been travelling in other countries that are really dangerous. In retrospect New Orleans is probably way more dangerous than a lot of those places, but at the time I felt like I could handle it. I was curious. I rode my bike over there, just meekly, one block in, and rode back. That one block was electric. I just loved it. There were people sitting on their stoops and the vibe was completely different. It was all black, and it was just vital. People were yelling across the street at each other. I loved it. I did that a couple more times over the next few months and then decided I wanted to buy a place. First I bought an abandoned lot near the [social housing] projects uptown, which I called Camp Congratulations. It was an open garden. I spent all my spare time buying plants, borrowing the hose from the neighbour—who charged me ten bucks every time, even though the water bill was included in her rent. I just kept planting, watering, working with the kids in the neighbourhood and teaching them how to care for the plants—it was completely unstructured.

EP: Was it like a green oasis?

KK: No, more like a derelict lot with some cultivated plants appearing willy-nilly. I would get frisked for being there—the police thought I must be a prostitute, because why else would I be there? I was totally dedicated to it but people kept stealing my plants. I had to learn to plant things that weren't flowering and had no leaves.

EP: You basically planted things that no one would want to steal.

KK: Exactly. So things grew from there. I was travelling across town to get there, so I decided to move into the 8th Ward. I got more organised and my vision got bigger.

EP: Tell me about the main art space you established. What sorts of projects went on there? Do you have some favourites?

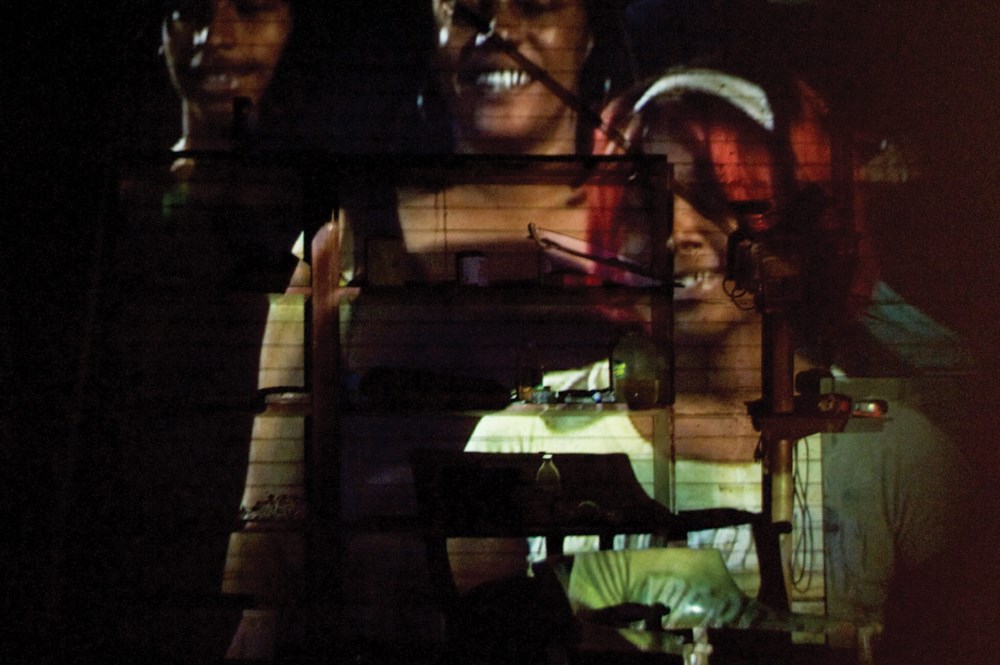

KK: There were all sorts. I loved Tony Oursler's project, where he videoed people in my neighbourhood reciting a poem and then projected that on the inside of this abandoned house that was all boarded up. You couldn't enter—it just had holes in the side of the house.

Sadly, one of the guys who was filmed got shot the day before the piece went up. So it became an instant neighbourhood memorial. It was really nice. It didn't last long—the projector got stolen. But for the 72-hours that it was up it was really special. I found it wild that the thieves ran off with a projector, never suspecting that the real value was in the form of a video by a super famous artist, which was now sitting in the sidewalk ditch where they’d tossed it. It’s like when I got broken into during an exhibition with $20 million of Rauschenbergs on the wall—and the thieves just took the $15 VCR. Who even has a VCR? But anyway, I did love Tony’s project. I think I have told you the story about the kids who illegally moved into one of my spaces?

EP: Tell me again.

KK: So I'm preparing for the 2008 New Orleans Biennial. I've got this Norwegian artist arriving, and I've sent her the floor plans for the space, and it’s all set to go. Meanwhile, we needed to put on a front door, because there wasn’t one. The Norwegian was going to use electronic elements like lights, and they would have been stolen immediately. The door was sort of pointless because there was this huge hole in the side of the building, but there was so much trash before you got to the hole, that no thief would bother. So at least I could close the front door. Anyway, I hired some guys to do that, but I had a million things happening at once, and I'm thinking, ‘Oh, the Norwegian has arrived with all of her crew.’ They’re in there working away, day and night, and I'm too busy to go look, plus I like to leave an element of surprise. Days pass, and I get a phone call, and it's the Norwegian artist. She's at the airport ready to be picked up. I'm like, ‘Shit. I'm so sorry. I'll be right there…’ What the fuck is going on in the house? I barge in and I'm like, ‘Who are you?’ And it's the most incredible art installation. It was made by the carpenter who put the door on and is also, secretly, an artist. He'd got all his friends involved and they had decided that they are part of the Biennial exhibition, too. I went, ‘You guys can't be in here. The artist is arriving. She's expecting to use this space,’ and they’re like, ‘Just take a look.’ It was incredible.

EP: What was it?

KK: They had made all of these secret portals. They'd plastered the walls with an unpublished novel by a former resident of the house. They created these slides from the attic, throughout the space. It was this secret wonderland—space after space, divided up. Incredible. Of course it took a carpenter's skills. Then in the back of this magical wonderland there were these golden floating things, all in pink light. They’d enclosed the entire back yard in this pink fabric. Anyway, it all worked out because the Norwegian preferred the other half of the building—which to me seemed completely unusable. That was the limitation of my own thinking, and that's what I loved about the project. I was constantly confronted with my own limitations. That's why I started calling it Life is Art. So the unknown artists ended up being the stars of the entire exhibition. They became the darlings of the local media. Eventually I realised that the beautiful pink fabric—they had actually stolen it from an art project funded by Brad Pitt. It was a series of pink tents in the Lower 9th Ward where there was no electricity, following Katrina. They were meant to represent future life coming back to this desolate area.

EP: This is still very close after Katrina?

KK: It was three years after.

EP: I'm getting the picture that the community there was welcoming to you, yet people also rampantly stole from you as well?

KK: Yeah, but the thief would come in the next day and sweep my floors because they felt so guilty. They're not doing it because they hate me. They're doing it because they need to buy crack.

EP: Right, and you're like, ‘That's fair enough’?

KK: Well, it's understandable, but inconvenient.

EP: Did you feel unsafe?

KK: Not really. I had a couple of scares. Once, I hadn't been there very long and a hand was reaching into my window. I didn't have any bars up yet.

EP: But you had a lock on your bedroom door, right?

KK: There was no bedroom. It was just a big old bakery, like a big, brick warehouse. It was just me in this space, me and my futon, and the front doors are locked, but the windows aren't. They're like these big, swinging, industrial windows. I see this hand start to come in my window and I just ran up and said, ‘Get the fuck out motherfucker!’ and slammed the pane on his hand. He got it out and ran. I'm pumping with adrenaline. I run out the front door. It's like six in the morning and he's gone. I run to the side and I see these footprints and the footprints have this very specific design. I ran out to the street and I see a guy and I run up to him and I say, ‘Let me see your shoes,’ and he’s so taken aback that he actually shows me the bottom of his shoe. I'm like, ‘You broke into my house you motherfucker. How dare you!’ and he's like, ‘What you talking about, bitch? I didn't break into no house.’ I'm like, ‘Come on,’ and I drag him over to look at the shoe print. He's like, ‘Nah bitch. Everybody be having these shoes’ and he puts his foot next to it and his is way smaller than the footprint with the identical print. I was like, duh, of course. If you're going to commit crimes you might like to have the same shirt, same pants, same shoes as everyone else, because it makes the description very difficult. I ended that experience with a great insight, and I actually became friends with that guy.

EP: Where is the criticism coming from at this point? Or was it not coming?

KK: Oh, it was coming. I honestly think that a lot of it had to do with just the way that I dressed, which my neighbours had no problem with. If I walked out looking bad, they'd say, ‘Girl, you don't look so good. You need to go in and brush your hair. You need to get it together, girl.’

EP: Was it about being white as well?

KK: The people who took issue with me were the liberal gutter-punks of New Orleans—mostly white, often educated people who, with a few exceptions, choose poverty and homelessness as a lifestyle or for ideological reasons—not my black neighbours. The black girls in my neighbourhood dressed up too, and looked fantastic. It's a glamorous culture and, in fact, that’s a lot to do with what egged me on to be more glamorous. But in the eyes of a gutter punk, it’s just not okay to be a white girl waltzing around a poor neighbourhood in high heels.

EP: Is it true to say that your intention was not to improve or change the community, but to draw out what was already worthwhile and beautiful about it?

KK: Yeah, definitely. But my intention at the time wasn’t even that. I went there because I liked it, and I liked doing my art projects there. My neighbours were doing what they did and I was doing what I did. I stayed out of their business. I didn't get involved with their drug deals or the police or any of that. But then of course curiosity caused them to have more engagement with what I was doing and friendships deepened. The social work with the kids was accidental. That was because the kids showed up trying to be a part of everything, getting in the way, and then you think, ‘Let's give them something fun to do.’

EP: There was no part of you that was like, ‘I'm going to show people the way out of a life of crime, or encourage these kids to go to school’?

KK: Not at all. I mean, once I made friends with them, then of course I would encourage a kid to do well in school. But that was definitely not the goal. In fact I helped one kid buy some goldenseal because he needed to pass a drug test for his job.

EP: What's goldenseal?

KK: It's a herb that flushes drugs out of your system. Clearly, I was not on a social work mission, and that also gave me some trouble, because it was perceived that I should be. Interestingly enough, that pressure very much came from art organisations—like the Warhol Foundation, for instance. Like, give me a break. It was so antithetical to Warhol's work. They hated me for something that was kindred to that lineage—irreverence. The very work that was pissing off the foundation, and that caused me to be blacklisted by them, was something Warhol would have loved. They asked me to throw this dinner for them. I ran a table down the centre of the block and put on this outrageous event. They wouldn't extend the budget for me to invite my neighbours for free, and my neighbours have no money. I figured you can't tell the difference between 200 and 240 people at a long table, so I secretly sold tickets to the event to a bunch of rich New Orleaneans to pay for any of my neighbours to come who wanted to. Then I gave my neighbours a choice: come to the dinner as a guest and get this five-course extravagant meal with entertainment, or work the event—a lot of people really valued the opportunity to work. They were all happy with that. Some chose to be guests, some to work. Coincidentally, my really good friend Losh—short for ‘lotion’ because he was just that smooth—had just died. He was the first person to take care of me in the neighbourhood and to get everyone else to take care of me. One of my artists at the foundation, Peter Nadin, paid for his funeral. Losh’s family and friends were so grateful that they decided to coincide his funeral parade—that’s how you celebrate someone’s life—with my dinner, which I’d dedicated to him. So they're marching their second line down through the neighbourhood and a lot of people are getting involved. The block is full, and some of these people are very disadvantaged, and some quite scary-looking. Not all of them had a seat at the dinner but they didn’t expect to—they were marching in the second line. They start to surround me and they’re chanting, ‘You lost one but you won a hundred, you lost one but you won a hundred,’ and I am weeping, I'm so happy. It was one of the highlights of my life. But while this is happening the Warhol guests—some loved it and understood it, but some got extremely uncomfortable. I was told that the number two [in charge] went back on the bus and wouldn't come out. I think it was very difficult for some members of the Warhol Foundation to see their privilege in the context of the disadvantaged, and to feel like they're part of this opulent, incredible display, in the ruins of an American ghetto.

EP: I can understand that would be very confronting.

KK: Confronting, yeah. But why shouldn't my neighbours get to have a five-course dinner? Normally these events happen at the Waldorf Astoria. For me the beauty was that my drug dealer neighbour is befriending a high-powered lawyer and talking about their legal experiences. All of this magic is happening as a result of the interface of cultures. That was what I found beautiful and it's what some others found offensive, and you can see why—but I don't think Warhol would have found it offensive.

EP: No. I don't think so either. So then why did you decide to become a marijuana farmer?

KK: It was an act of desperation. But I also really loved the idea. It was a joke at first, then suddenly I thought, actually that kind of makes sense. I decided to do it in the moment, while I was giving a talk to Natalie Jeremijenko’s students at NYU. I was really struggling post-GFC to keep my organisation afloat. This was around the beginning of 2009, and I'm suffering. I've lost my fancy side-job as architect to this billionaire. So now I've got nothing to keep me going, no personal income, and I’m struggling because members of my foundation are not seeing eye-to-eye. My patrons have gone into survival mode. And the students asked me. They're looking at my slides, and they love the projects, and they’re going, ‘This is so great, how do you fund a non-profit?’ and I said, ‘Do you really want to know? Sex and drugs. That’s the only way, unless you’re independently wealthy or really good at kissing ass and conforming.’ I said it as a joke, because a lot of the private patrons are men and they, you know… I'd just been offered to have my entire program funded by a major developer and billionaire in New York if I just slept with him.

EP: My God, really?

KK: Yep. He just laid it out. I was sent to him by members of a fellow organisation, who were my heroes really, and they’d organised for me to meet him in New York. We go to lunch and he leans across the table, and he’s got his cuffs embroidered to say ‘No guts, no glory’, and he says, ‘Alright, what's your operating budget?’ and I say, ‘$275,000 a year.’ He's like, ‘Oh easy. Handled.’ We're in Pastis, so we’re really squeezed in and everyone can hear what we're talking about. I said ‘Really? That's amazing!’ He's like, ‘Yeah, right. Done. Alright, let's go to the hotel.’

EP: Oh my God.

KK: I said, ‘Where?’ and he said, ‘To the hotel. Let's go.’ ‘What do you mean? I don't want to go to the hotel,’ and all the people next to us are listening in, and I'm just trying not to break into tears. I told him no, and he said, ‘Alright—no play, no pay.’

EP: What a cunt. Sorry but that’s the only word for it. I have nothing against an honest transaction, but not when it’s mean and bullying like that.

KK: It was horrible but he also had that cool outlaw thing going on. I thought I might be able to turn him around but in the end I failed. Then the other guy that I was connected with was a former director of a very important museum in New York and when I went to meet with him he kept serenading me with Beatles songs, and wouldn't talk business. I was like, ‘That's really wonderful. You're a great musician. Can you put down the guitar now so we can talk about the project?’ What a bunch of dicks.

EP: So then you were like, 'Okay, so sex isn't working out. What about drugs?'

KK: Sex would have worked wonders if I were willing. If I'd liked the guys or something, great, but… Yeah, so as the words came out of my mouth to these NYU students I had an epiphany. Part of why I was so broke was because I was trying to keep this property in California afloat that I’d bought with my friend Jaohn when the market was booming. We had 120 acres sitting there, doing nothing. The laws in California had just changed so you can legally grow medical marijuana. So if I create a non-profit to grow marijuana and sell it to fund the arts, then I'm golden, and I can say goodbye to all these creeps and weirdos and uptight fascist institutions. And it's performance art simultaneously. That really sums up ‘life is art’ for me, because it's functional action in the world, but the whole thing is a conceptual artwork, and therefore completely un-boring. So in that context going into the business administration office and registering my new business and filing paperwork with the Public Works Department and going to see the lawyers and judges to discuss my legal status is all part of the work, and therefore very exciting. The more boring and tedious the process, the better.

EP: I liked your quote in the New York Times: ‘This whole game of finding support just seemed so childish, so I decided to grow up and become a marijuana farmer.' You met David around this time?

KK: I’d met him a few years before but we became serious around this time. We were courting from afar but he did come out to the farm, which was traumatic for him because I had no toilets. He doesn't like camping after his experiences as a berry picker in the bush. Some kind of traumatic childhood experience.

EP: I have so many questions about the way your ideas about art and David's ideas interact, I don't even know where to start. Firstly, how has your approach changed since meeting him and moving to Tasmania?

KK: My experience with art and the kind of projects that inspire me are the same, but everything's become easier and higher production value. I'm not hitting my head against the funding wall, which is a huge, huge relief. It has taken time to come to that place. At first I didn’t know what to do or how to do it and I felt nervous about imposing myself and my ideas on his world and in particular on the other Mona curators. The museum hadn't opened when I came here but it was close, and it was this fully functioning organism that I had to find a place in, without disturbing.

EP: But also disturb.

KK: The truth is I didn't want to disturb it. Even on opening night I took over the spaces that weren't part of the museum, the electric room and the pipe cavern. I started in a very small way, and then as time has passed, I feel native to the ecosystem.

EP: There are a lot of differences between your worldview and David's, but what are the similarities?

KK: We both like the unexpected. That element of surprise in art gets both of us. Neither of us stick to a genre. We tend to agree on pure aesthetics projects, minimalist projects, but we clash on craft. Contemporary craft projects don't do it for me as art, even though I may admire them as objects. But he sees it as art, and that's really funny because of course I'm producing art that most people would say is not art. I'm challenged when the medium is traditionally craft, but being practised in a contemporary way. Like Patrick Hall, for example.

I love Patrick's work. He's got this set of drawers made of books in our apartment in Melbourne that is sublime. Yet, I don't look at it and say, ‘That's great art.’ I know that he's integrating stories and there is a richness and depth, and David revels in it. He loves it. It's absolutely beautiful but it doesn’t have the certain conceptual play that I like.

EP: What does constitute great art for you, then?

KK: There's an ‘ah-ha’ moment. Or else a stunned silence. There's an enforced change to my physiology. Ideally it offers a completely new way of seeing the world. So there's a mind shift as well.

EP: Is there anything in Mona's collection that meets these criteria?

KK: I love so many pieces in the collection but one of my favourites is the Paul McCarthy video, Painter, 1995.

EP: Really? I just finished writing a piece on that. I can't believe that's what you chose. That's like, the ugliest thing to me.

KK: It's really ugly, but it's addressing social ugliness. It sticks it to the art world and the art world really deserves it. What I love about David, too, is that he is not a slave to that hierarchical, self-preserving culture. I just love that about him. I loved it the moment I saw him. We were at Art Basel, which is the epicentre of that whole ugly scene—in addition to being an epicentre of great art. I saw him from across the room and I could tell that he did not give a fuck about any of the rules and codes of behaviour that were so strict in that setting. I could just tell that he was free. I mean, it's not that hard to see. He's, like, wearing torn jeans and he's got some, you know, ‘Fuck God’ t-shirt on.

EP: ‘How stick man became extinct.’

KK: It was instantly adorable and very seductive.

EP: I know that you're ironical about your new-ageism, but there is still a part of that background that persists. That is the polar opposite of how David thinks about the world. How do those worldviews coexist?

KK: It's easy because in some ways I find new-age culture repulsive. I enjoy taking the piss out of that way of being, to the extent that sometimes David and I swap places. We watched this jazz musician the other night and the guy was talking between each set, and he was like, ‘The way I see it, we're all just spinning on this little green ball called the planet. Please don't hurt her. Please protect the planet.’ I'm trying not to laugh, but David was totally enthralled. He says he's this strict atheist and can't stand magical thinking, but a number of his close friends, his close lady friends in particular, are magical thinkers. He enjoys the company of them, and that's because they're more fun and life is better and more interesting when you think magically. I wish I did it more. I wish I hadn’t become as rational as I am, because when you do believe that coincidence is a window into the inner workings of the universe, that there is a plan, and that everything is falling into place—then you can really have fun, because you're interpreting things as signs and you can revel in it all, just laugh and enjoy it, and it creates a state of bliss. That's why new-agers are blissed out. My reason doesn't allow me to do that anymore, but I still pick friends who do.

EP: I have a real empathy with that. I always had a religious feeling about academia. Postmodernism and an intellectual kind of feminism were my governing systems for making sense of the world, even though I believed on some level that the relation to reality was tenuous.

KK: I don’t know what to say about that, Elizabeth. That sounds a little disturbed. The new-agers would say that science is David’s governing system, but actually science is reality’s governing system.

EP: The postmodernists would say that too. Postmodernism and new-ageism are human ways of seeing the world because they are emotional and intuitive and self-perpetuating. The way science reads reality is so much harder, and counter-intuitive. I’ve learned to appreciate it, and I think it’s terribly important, but I’ll never really inhabit it because it’s not human enough for me. That total absence of involvement and agenda is hard for me.

KK: But that’s what the new-age methodology is—open-mindedness. It's funny because I have thought before that the Buddhist state of non-attachment and openness and allowing the information of reality to just flow through you is very much like a scientist's methodology where you can't be attached. You can't have an ego in it. You can't have an opinion about it, you have to revel in reality as it presents itself and as you discover it, and allow that to be exactly what it is, and record the facts.

EP: I can see how you and David arrive at a similar point on certain matters, but how you get there is completely different.

KK: These days I feel pretty rational but I like to take the things I learned from living in societies that were not rational, and apply them to mainstream society, because mainstream society does have a lot of aesthetic problems and a lack of community.

EP: Okay. So the Embassy project. It came from a twin impulse in you. You wanted to respond to the gun-violence issue in America but you wanted to do so in a way that was respectful to your pro-freedom attitude.

KK: When I moved to the US [mainland] in my late teens I was basically adopted by these libertarian, psychedelic adventurers like John Perry Barlow and the biospherians, and they instilled in me some libertarian values. My attitude was pro-freedom anyway. I dropped out of society, as we talked about. So I always felt like gun control didn't make sense and should be a matter of choice for every reason, all the way down to spiritual reasons. The Dalai Lama even says that guns are a tool for learning responsibility. Then again, he also thinks that there are multiple lifetimes and you get to keep working it out, so maybe if he understood you only get one, he might think differently. But still, I believed that it should be a choice, and that the cure for violence was education. Society should confront the disadvantage that breeds gun violence, and infuse opportunity and education into the ghettos. And all the while that I held this view, these guys that I knew and loved were dying around me. Then one guy that I really loved, who was like a son to me… I mean, we hung out all the time. He wasn't even part of the gangs. Someone decided for his benefit to initiate him into the gang so that he wouldn’t be such an outcast reject, to give him some respect, and they accidentally killed him.

EP: Oh my God.

KK: I think they didn't know you could kill someone if you shot them in the leg. He bled to death and the police wouldn't let his friends touch him, so they couldn't clamp the blood. So we lost wonderful Ray, who was such a talent and delight. Even then I felt that the solution wasn't to make guns illegal. But then I moved to Australia and it was kind of a slap in the face. Gun control works. I had no choice but to acknowledge that it works. I had these opposing realities and I was struggling to let them coexist. Then one day I had this realisation that if I could use private enterprise, the libertarian value of the free market, to create gun control by offering private money for guns, then I would be addressing the gun violence issue and holding on to my pro-freedom ideals. Most importantly I would be shining light on my own hypocrisy—those two duelling realities that coexist within me. So that's what the Embassy was about. I asked David to be the source of private funds, and he agreed—sex is working out after all. It was healing for me too because it was an opportunity to go back to my old neighbourhood. We rented a place—a car wash on my corner, a block and a half from my old house. The owner of the car wash was this cool rapper dude called Big Ace BO$$ CEO. We made a deal which involved putting a new roof on the building and went in and transformed the interior into a ritualised gun-sale site. The idea was that the interior of the car wash would be this jewel-box space, absolutely beautiful, done out in precious materials—gold leaf and crushed velvet and mirrors. It was referencing the interior of coffins, which are often lavender silk. So everything was lavender, as a stunning contrast to the external environment, which was very run down.

EP: How important was the measurable outcome—the number of guns that you removed from the street?

KK: It wasn't important. I did think, ‘If we had tonnes of money could it actually make a difference?’ I believed that it could, and we did get a kick-ass Berkeley statistician to model it, but for me it didn't matter if it worked or not. It was about shining light on the problematic features of libertarianism. I also loved the drama and the pageantry of this living installation where people ritualistically surrendered their gun. The idea was that they would be transformed through the process because the art space was beautiful, temple-like, reverent and healing. To turn in your gun you had to go step-by-step through this space, encounter an opera singer and a cellist, and then receive your cash. So you would be cleansed in a way. Stage one of the Embassy was about exploring the ideas and creating links in the community and sparking things that could lead to something that does actually solve the problem. But the school that we spoke about earlier, which evolved from the Embassy, is very much about solving the problem. That doesn’t mean it’s abandoned its identity as a work of conceptual art. But it is about genuine outcomes as well. The longer I exist in this world the more I feel the need to improve it and change it. Very un-Zen, but that’s where I’m at.

EP: So what about Eat the Problem, this notion you have about eating invasive species? Is it a genuine response to an ecological problem, or is it more about that sense of community pageantry?

KK: Eat the Problem is about the radicalness of the idea. It gives you a little shock and thrill when you think about eating some of these things. They're not appealing. But the fact that you're doing your environmental duty by consuming them is entertaining. At the same time, there is a true problem that I am trying to shine light on. Of course, I find most environmental campaigns completely repulsive. Aesthetically repulsive. Eat the Problem is a rebranding of an environmental sentiment.

EP: The environment needs a good brand manager.

KK: It needs a major brand makeover. Eat the Problem is part of that. It's about making environmentalism a little bit cool and a little irreverent, bringing in artists, gourmands, and the great chefs of the world, and just having some fun with this idea. But it is a genuine criticism of us eating cows, which I wouldn't want to talk about in a normal context because it's boring. But really we shouldn't be eating cows because it is really bad for our future.

EP: And theirs.

KK: Yes. I care about that, and that's why I don't eat them. But also for purely selfish reasons we shouldn't be eating them because we are making big problems for ourselves. By consuming an invasive species instead, you're engaging in sustainable self-perpetuation. The core idea is one that I love, and that drives so much of what I do—turning shit into gold. You take a problem and you transform it into an asset and in doing so you eliminate waste. For example I am talking to an engineer who's working on the new Mona hotel but it turns out he's also invented an environmentally friendly surfboard by combining Eucalyptus fibre with some other harmless materials. I'm talking to him about what he might able to do with cats claw, which is swallowing up the entire south east of the US and destroying everything in its path. If that could be turned into fuel, food or a plastic alternative, then great, because we're making such a huge mess generating these things and they produce so much waste. An invasive species becomes free fuel, free energy, a free resource—and even an engine for creating jobs in the lowest employment areas, where the cat’s claw happens to grow. Ideally there’s a new gold rush, and our consumption becomes an asset. Suddenly our problem is a market that preserves historic architecture and native ecosystems as a by-product.

EP: What's an example in Tasmania of an invasive species that's causing significant ecological damage?

KK: The sea urchin. The sea urchin needs to get way more popular on the menu. And they are delicious. They basically vacuum the sea floor, killing everything in sight. They become a monoculture. The whole sea floor will just be sea urchins. The starfish is doing the same thing but that's trickier to turn into a delicacy. We tried, at the Mona market (MoMa).

We did starfish on a stick. They weren’t very popular. So then we freeze-dried them and turned them into Christmas ornaments, and they were really ugly. Then it turned out that ground-up starfish make a good filter for mercury, but again, that's kind of a boutique solution. So we haven't really thought of anything for the starfish. But sea urchin, on the other hand, is an incredible culinary delicacy. I went to Corsica to this tiny restaurant and the chef brought out this bowl of steaming sea urchins and the locals are just eating them spoonful by spoonful, shell after shell. Japan pays a fortune for it. It’s just a matter of changing eating habits. But ultimately it's about transforming a flaw into a feature.

EP: If we can do that in all walks of life we've got it nailed.

KK: Exactly. They are just starting to do more with invasive possums in New Zealand. In New Orleans—why isn't the nutria fur industry huge? I love wearing fur but I feel extremely guilty about wearing it. Plus David won't buy it for me anymore.

EP: He's so selfish.

KK: He is so selfish. He’s a selfish, selfish man. He feels guilty about the fact that he did buy me one early on in the relationship when he didn't want to risk scaring me away. I wear it all the time but lie and tell people it’s velvet.

EP: It makes me think about what the tech guys would say—‘Is it a bug, or a feature?’ It makes me think about relationships as well. To turn the flaw of your loved one into a feature rather than a bug, that's the goal.

KK: It can happen physically very easily—the features that you didn't like at first become what you adore. It shouldn’t be, ‘Let's get rid of this stuff by eating it,’ it's more, ‘Wow, we hit the jackpot, but we're blind to it.’ Because of the nutria problem in New Orleans I can wear as many fur coats as I want, guilt-free, because they're being culled and bounty hunters are being paid $8 a tail to shoot them and leave their carcasses floating in the swamp. That's free fur. It's also free meat, at least for dog food. But I bet a great chef could make it taste really good. Paul Prudhomme had a go at it.

EP: So with the Eat the Problem cookbook, do you want people to actually make the recipes?

KK: Alfredo Jaar is proposing fascists as his invasive species. So you wouldn’t make that one. I have to say almost every artist came back with humans as an invasive species. They were all like, ‘I have this really radical idea. I’d like to use humans as the invader!’ And I’d have to find some tactful way of telling them that the idea maybe wasn’t that radical. But there are real recipes in there as well. It runs the full range from silly to sincere and impossible to completely realistic.

EP: How did you select your contributors?

KK: Using my typical God-as-the-curator approach. Chance meetings, late night conversations in a bar. Emily's pest-control guy, who showed up at her place and said ‘Just don't make me vote for the Greens’ and I'm like, ‘I bet you he'd be great to interview.’ Plus finding out who’s doing interesting work in this area and writing to them and asking them.

EP: Ok so I feel like I’m getting to the end of my questions. Do you feel like we have covered enough?

KK: The part I don't feel like we really got was the David part.

EP: Really? I loved what you said about David.

KK: I love David. He's so cute.

EP: He's a shit though.

KK: Oh my God. He can be such a shit. He’s super sweet too.

EP: I’ve got a question for you. Is being ‘First Lady of Mona’ kind of like a work of performance art for you?

KK: Yes. That's the way that I can handle it and like it. I have to turn it into a performance. And yeah, I get a kick out of it. I bought myself a giant pearl necklace. All first ladies have pearl necklaces. I found one that's one huge pearl in this kind of aggressive setting. Like, totally wrong. I crack up every time I put it on. I wear it to ladies lunches—I get invited to all of these political-lady fundraiser lunches.

EP: That role must come with some frustrations as well?

KK: On the one hand, the First Lady title is accurate—I'm doing social work, Mona-style. It's also painful. There are a lot of problems with it as a title. I celebrate the absurdity of it but I don’t know if I’d have the guts to, say, put it on a business card.

EP: I find it incredibly brave, the fact that you're prepared to do the stuff that you do knowing that a lot of people won't get the joke.

KK: It's terrifying. Sometimes I chicken out.

EP: I think you chicken out less than you think you do.

KK: The other day we had a lunch in The Source and I wore this… it was so wrong. Just wrong on every level. I was wearing this Alexander McQueen jumpsuit skirt thing that I bought in London. It gave me a giggle. I looked like the ultimate nouveau-riche, kept woman. It had a very visibly Alexander McQueen pattern. It was tacky but great. So then I put on these obscenely high white heels and I came to lunch and I was performing. But then I got terrified because I realised no one at the lunch is going to get the joke. They’re going to think that I’m a nouveau-riche, kept woman—which is also true on one level.

EP: That’s quite out there. Seriously brave.

KK: It's accommodating paradox.

EP: ‘If a joke is made in a forest and there’s no one around, is it still funny’ kind of thing. I would need some kind of peer sanction—some sort of safety net.

KK: The closer the person who doesn't get it is to your social sphere, the more terrifying it is. If a conservative politician is at the lunch table and he thinks I'm rich trash, that's great, because that's part of my performance. But if a cool, contemporary art curator from New York comes to the table and doesn't get it, then that's terrifying and painful.

EP: I don't really do this anymore, but like I used to kind of deliberately flout grammar rules. When someone who I considered to be a good writer was like, ‘You’ve made a mistake in that sentence’ it really hurt. But someone who is in a completely different world to me I didn’t care about. You need some kind of audience for it to work.

KK: Yes, it's exactly the same thing.

EP: James and I have this disagreement about how jokes work. I like stuff where people engage with an offensive notion in order to highlight how absurd the offensive notion is. Like racist and sexist jokes in The Office. The joke is on the racist and sexist person. He hates it, because he says no matter how much you’re distancing yourself from the offensive notion you are ultimately enacting and perpetuating it.

KK: It’s true though, you kind of are.

EP: He’s tremendously sincere. It’s a feature, not a bug.

KK: That’s why I want to explore these character roles, these uncomfortable zones. You shine a light on your own hypocrisies and hopefully transcend them in the process. But you’re also inhabiting them. That's what art is for. Art is for shining a light on the things we're grappling with in a way that adds levity and allows us to be with it and celebrate it. We're with it. Here it is. You know?

*Rouge Battery, 2014 actually cost $3 million.

**Kirsha would like it to be understood that she does not currently engage in psychedelic use and is a clean-living, responsible mother. And she will never buy a new fur coat again unless it is made from culled invasive animals.